MIT Engineers Develop 3D-Printable Aluminum Five Times Stronger Than Standard Alloys

As a challenge, Olson asked the class to create an aluminum alloy stronger than any 3D-printable aluminum developed at the time. Aluminum’s strength, like that of many materials, is largely governed by its microstructure: the smaller and more densely distributed its microscopic building blocks, known as “precipitates,” the stronger the resulting alloy.

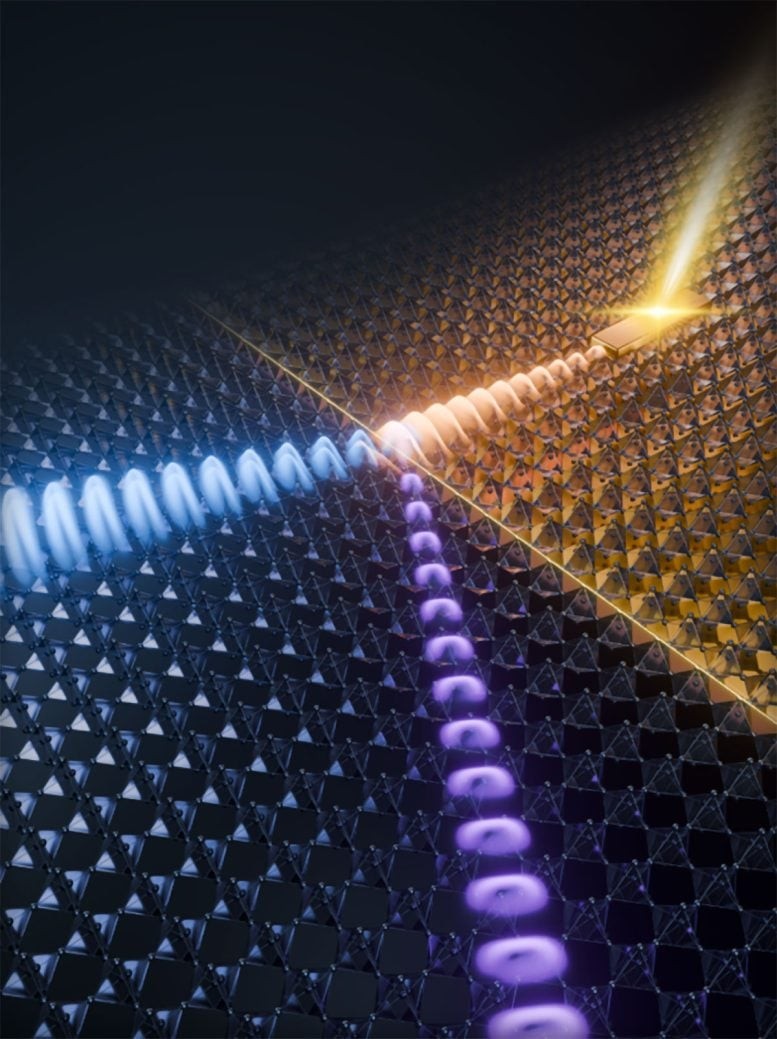

Figure 1. MIT Creates Ultra-Strong 3D-Printable Aluminum.

Guided by this principle, the students used simulations to systematically mix aluminum with different elements in varying concentrations, predicting how each combination would affect strength. Despite these efforts, none of the designs surpassed existing materials. By the end of the course, Taheri-Mousavi began to question whether machine learning could succeed where conventional simulations fell short. Figure 1 shows MIT Creates Ultra-Strong 3D-Printable Aluminum.

“At a certain point, material properties are influenced by many factors interacting in complex, nonlinear ways, and it becomes difficult to see the path forward,” Taheri-Mousavi explains. “Machine-learning tools can highlight where to focus—identifying, for example, which elements are driving specific features. That makes it possible to explore the design space far more efficiently.”

Layer by Layer

In the new study, Taheri-Mousavi picked up where Olson’s class had left off, this time aiming to uncover a stronger aluminum alloy formula. She turned to machine-learning methods capable of rapidly analyzing data such as elemental properties, revealing key correlations that could guide the design toward superior performance.

By evaluating just 40 different aluminum-based compositions, the machine-learning model quickly identified an alloy predicted to contain a higher volume of fine precipitates—and therefore greater strength—than any found in earlier studies. Remarkably, this result outperformed outcomes from more than one million traditional simulations conducted without machine learning.

To manufacture the predicted alloy, the team determined that 3D printing was preferable to conventional casting, where molten aluminum cools slowly in a mold, allowing precipitates to grow larger and weaken the material. In contrast, additive manufacturing enables rapid cooling, preserving the alloy’s fine microstructure.

The researchers focused on laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), a 3D-printing technique in which metal powder is deposited layer by layer and selectively melted by a laser. Each thin layer solidifies almost instantly before the next is added. This rapid cooling, the team found, was essential for creating the small-precipitate, high-strength aluminum alloy predicted by their machine-learning approach.

Testing the Predictions

To validate their design, the researchers commissioned a custom powder formulation based on the new alloy recipe—a blend of aluminum and five additional elements. The powder was sent to collaborators in Germany, who printed small test samples using an in-house LPBF system. These samples were then returned to MIT for mechanical testing and microstructural analysis.

The results closely matched the machine-learning predictions. The printed alloy proved to be five times stronger than its cast equivalent and 50 percent stronger than alloys developed using conventional simulation techniques. Its microstructure showed a significantly higher density of fine precipitates and remained stable at temperatures up to 400 °C—an exceptionally high threshold for aluminum alloys.

“Our approach opens new possibilities for designing alloys specifically for 3D printing,” says Taheri-Mousavi. “My hope is that one day, airline passengers looking out the window will see engine fan blades made from these aluminum alloys.”

By evaluating just 40 different aluminum-based compositions, the machine-learning model quickly identified an alloy predicted to contain a higher volume of fine precipitates—and therefore greater strength—than any found in earlier studies. Remarkably, this result outperformed outcomes from more than one million traditional simulations conducted without machine learning.

To manufacture the predicted alloy, the team determined that 3D printing was preferable to conventional casting, where molten aluminum cools slowly in a mold, allowing precipitates to grow larger and weaken the material. In contrast, additive manufacturing enables rapid cooling, preserving the alloy’s fine microstructure.

The researchers focused on laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), a 3D-printing technique in which metal powder is deposited layer by layer and selectively melted by a laser. Each thin layer solidifies almost instantly before the next is added. This rapid cooling, the team found, was essential for creating the small-precipitate, high-strength aluminum alloy predicted by their machine-learning approach.

“Sometimes we need to rethink how materials can be made compatible with 3D printing,” says study co-author John Hart. “In this case, 3D printing itself becomes the advantage. The extremely fast cooling after laser melting produces a unique set of material properties that simply aren’t achievable with traditional methods.”

Source:SciTECHDaily

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2025), MIT Engineers Develop 3D-Printable Aluminum Five Times Stronger Than Standard Alloys, AnaTechMaz, pp. 337