Quantum Material Senses Minute Mechanical Strains

A new sensor developed at Nanjing University, China, can detect mechanical strains more than an order of magnitude weaker than previous devices. The sensor operates by detecting changes in single-crystal vanadium oxide materials as they transition from a conducting to an insulating phase. This innovation could find applications in electronics engineering and materials science.

For detecting tiny deformations in materials, the ideal sensor would undergo a clear, measurable transition when even a very weak strain is applied. Phase transitions, such as the shift from metal to insulator, are ideal for this purpose because they cause a significant change in the material's resistance, generating large electrical signals that can be easily measured to quantify the strain.

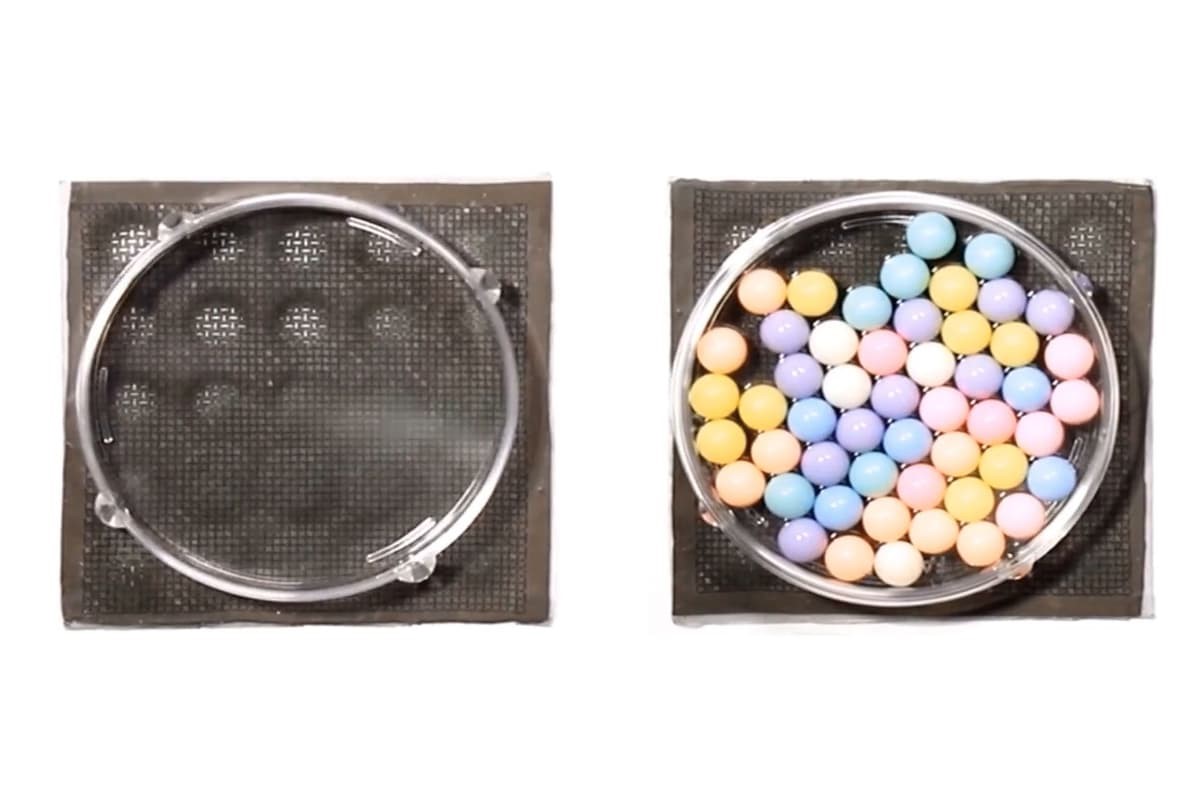

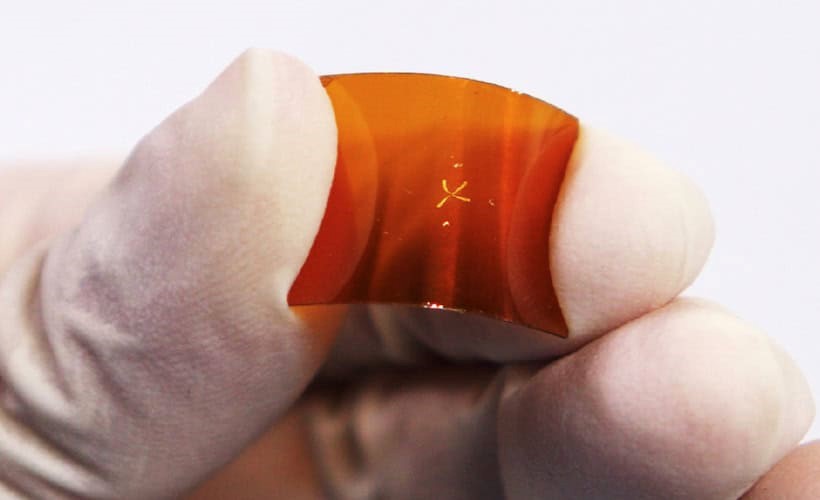

Figure 1. The Flexible Mechanical Sensor

Traditional strain sensors, however, rely on metal and semiconductor compounds, whose resistance changes little under strain, making it difficult to detect weak strains, like those caused by the movement of microscopic water droplets. Figure 1 shows the flexible mechanical sensor.

A research team co-led by Feng Miao and Shi-Jun Liang has overcome this limitation by developing a sensor using the bronze phase of vanadium oxide, VO2(B). Initially, the team focused on studying this material to understand its temperature-induced phase transitions. However, they discovered something unexpected along the way. "As our research progressed, we found that this material responds uniquely to strain," Liang explains, prompting the team to shift the focus of their project.

A Challenge in Fabrication

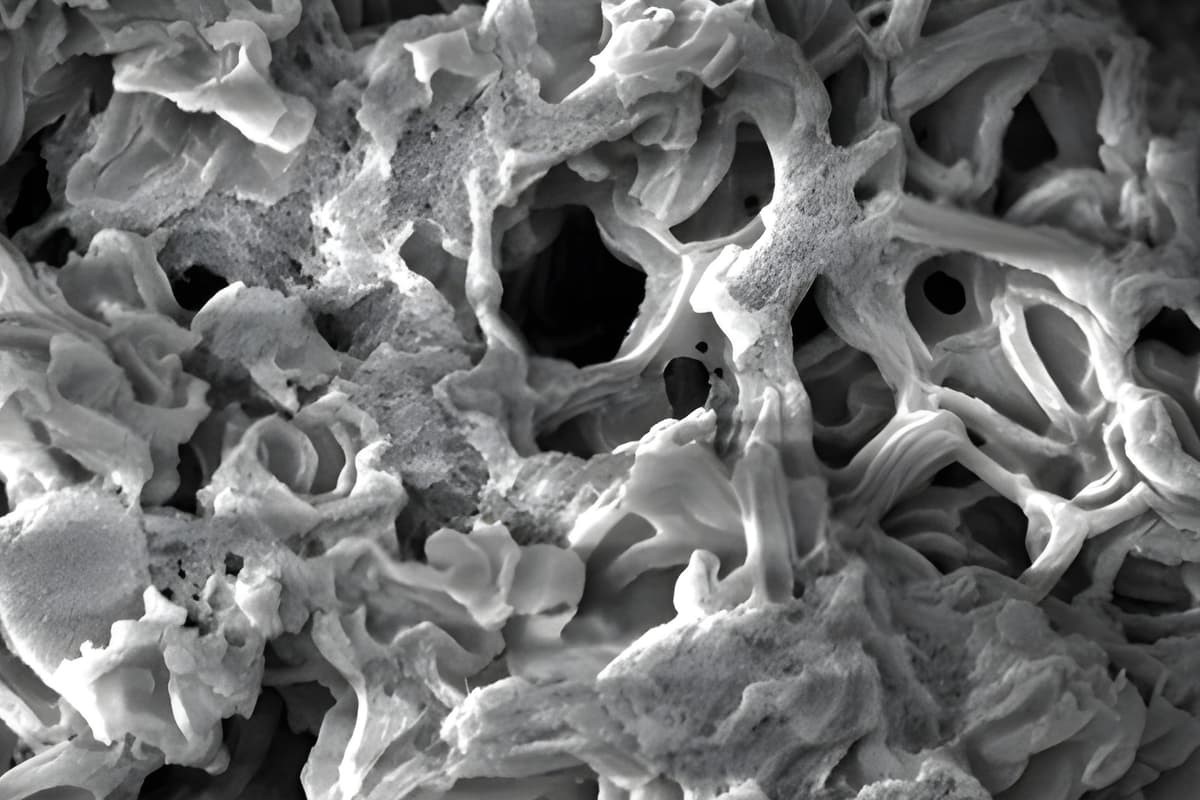

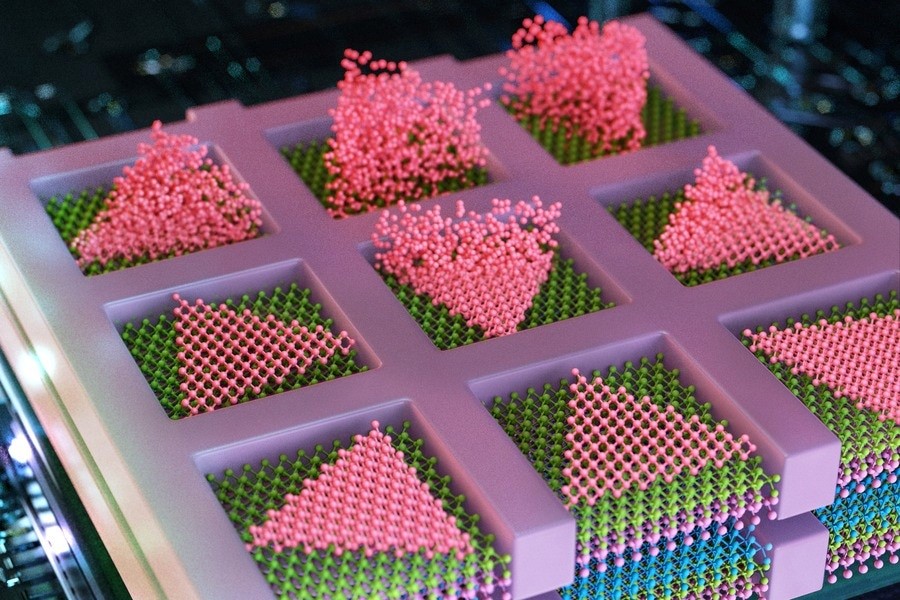

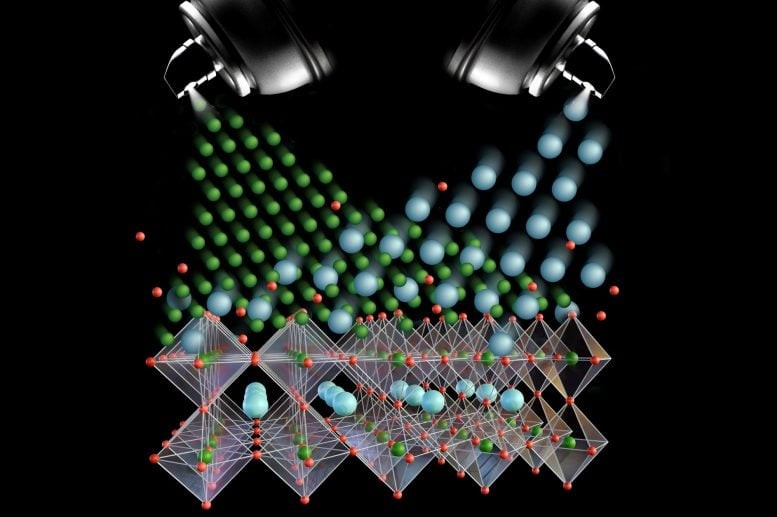

The complex structure of vanadium oxide made fabricating a sensor from this quantum material one of the team's biggest challenges. To create their device, the researchers at Nanjing University employed a specially adapted hydrogen-assisted chemical vapor deposition micro-nano fabrication process. This technique allowed them to produce high-quality, smooth single crystals of vanadium oxide, which they characterized using various electrical and spectroscopic methods, including high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM). The next challenge was transferring the crystal from the SiO2/Si wafer on which it was grown to a flexible substrate made of smooth, insulating polyimide.

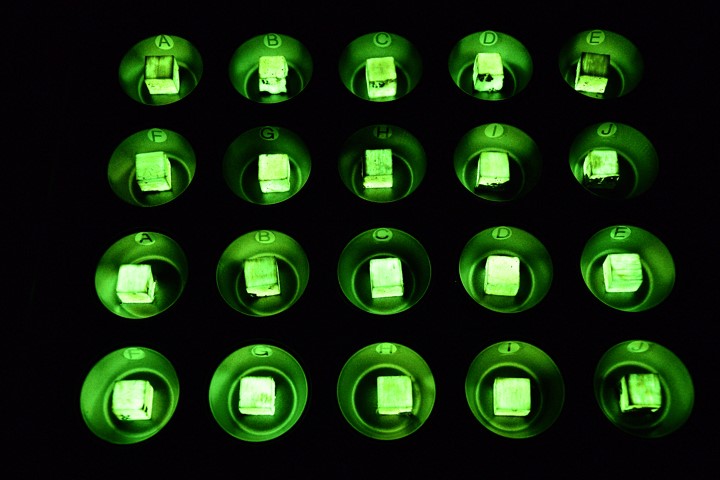

Once this was achieved, the researchers placed the polyimide substrate with the VO2(B) crystal into a customized strain setup. They attached the device to a specially designed socket and applied uniaxial tensile strain by vertically pushing a nanopositioner-controlled needle through the material. This action bent the flexible substrate and curved the sample's upper surface.

The team then measured how the current-voltage characteristics of the mechanical sensor changed as strain was applied. When no strain was applied, the channel current of the device was 165 μA at a bias of 0.5 V, indicating it was in a conducting state. However, as the strain increased to 0.95%, the current dropped to just 0.50 μA, signaling a shift into an insulating state.

A Remarkably Significant Change

The researchers also examined the device’s response to intermediate strains. They observed that initially, the resistance increased only slightly as strain was applied. However, when the uniaxial tensile strain reached 0.33%, the resistance surged, and thereafter, it rose exponentially with increasing strain. By the time the strain reached 0.78%, the resistance had skyrocketed by more than 2600 times compared to the strain-free state. This substantial variation is attributed to a strain-induced metal-insulator transition in the single-crystal VO2(B) flake, as explained by Miao. "As the strain increases, the entire material transitions to an insulator, resulting in a significant increase in its resistance, which we can measure," he says. Furthermore, this resistance change is stable and can be measured with the same precision even after 700 cycles, confirming the technique's reliability.

Measuring Air Currents and Vibrations

To evaluate their device, the Nanjing University team used it to detect the minute mechanical deformation caused by placing a micron-sized plastic piece on it. In addition to sensing the slight pressure exerted by small objects, they found that the device could also detect subtle airflows and pick up tiny vibrations, such as those caused by the movement of small water droplets (around 9 μL in volume) on flexible substrates.

“Our research demonstrates that quantum materials like vanadium oxide hold great promise for strain detection applications,” Miao says. “This could inspire further exploration of such materials in fields like materials science and electronic engineering.”

This study, published in Chinese Physics Letters, serves as a proof-of-concept, Liang notes. Future research will focus on growing large-area samples and investigating ways to incorporate them into flexible devices. “These advancements will help us develop ultra-sensitive quantum material sensing chips,” he concludes.

Source:PhysicsWorld

Cite this article:

Janani R (2024), Quantum Material Senses Minute Mechanical Strains, AnaTechMaz, pp. 78