When Atoms Break the Rules: High-Entropy MXenes Challenge Materials Science

By disrupting atomic order, scientists have crafted a new class of MXenes—nine metals woven into a single atom-thin sheet, forming a chaotic yet promising mosaic. This breakthrough could transform how we engineer materials built to endure the most extreme environments on Earth and beyond.

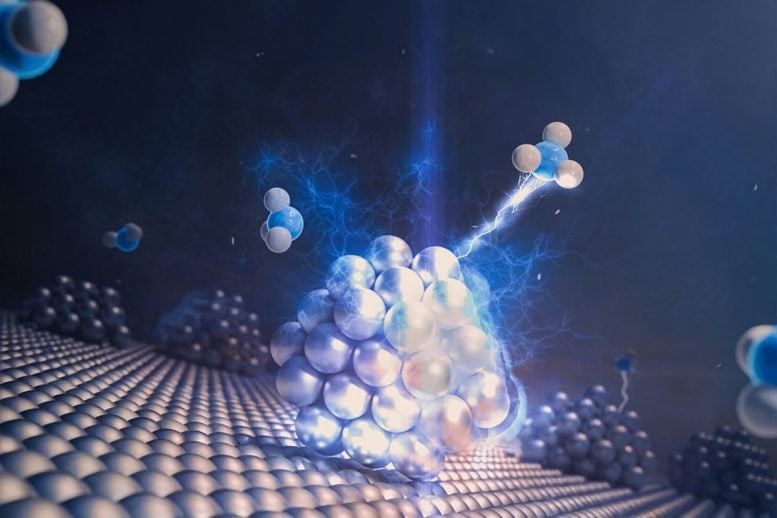

Figure 1. When Atoms Defy Order: High-Entropy MXenes Rewrite Materials Science.

Throughout history, materials science has celebrated symmetry and stability — crystals whose atoms lock together like endless tiles across an infinite floor. That order has long been the source of strength, conductivity, and control, both in the lab and in the real world. Yet in one remarkable family of carbides, the script flipped. Here, chaos didn’t destroy structure — it became the source of it, as if disorder and order were two sides of the same design. Figure 1 shows When Atoms Defy Order: High-Entropy MXenes Rewrite Materials Science.

That paradox arose from a collaboration between researchers at Purdue and Drexel Universities, who set out to see what would happen if they pushed a well-known family of layered carbides to its limits. Their idea was bold in its simplicity: take a material prized for its atomic precision and force it to host multiple metals in the same structure — to see how far it could stretch before collapsing into chaos.

But the collapse never came. Instead, the material hit a tipping point. Beyond a certain threshold, the expected order broke down — and entropy, rather than destroying the lattice, stabilized it. What appeared to be chaos turned out to be a new kind of order, revealing an unexpected pathway to stronger, more versatile materials.

MAX Phases: The Scaffolding Beneath

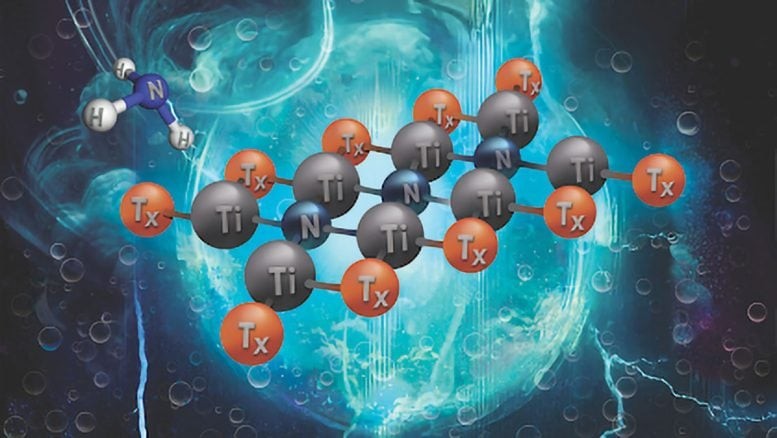

To understand this breakthrough, we need to rewind to the 1970s, when scientists discovered a curious family of layered ceramics known as MAX phases. Their formula — Mₙ₊₁AXₙ — describes a structure of transition metals (M) bonded with carbon or nitrogen (X), separated by layers of “A” elements such as aluminum or silicon.

MAX phases were remarkable because they combined properties rarely seen together. They possessed the toughness of ceramics, capable of withstanding heat and wear, yet conducted electricity like metals. Their atomic architecture — alternating layers of metal and non-metal — made them both stable and strangely flexible, as if inviting future disruption.

For decades, MAX phases were valued for their resilience and conductivity. But their true potential emerged in 2011, when researchers discovered that by selectively etching away the “A” layers, they could peel these structures into sheets just a few atoms thick. These two-dimensional derivatives became known as MXenes — materials that would soon challenge our deepest assumptions about order, entropy, and the design of matter itself.

mxenes: When Surfaces Became the Story

While MXenes inherited the toughness and conductivity of their MAX-phase parents, their true power emerged in what lay exposed. When the A-layers were etched away, scientists discovered that the surfaces of these sheets could be chemically tuned — decorated with oxygen, hydroxyl, or fluorine — to adjust their behavior for different purposes.

What followed was the birth of a new class of two-dimensional materials, more adaptable than graphene or any of its atomic peers. MXenes could disperse in water, self-assemble into films, and have their properties reprogrammed almost at will. Within just a few years, they were being tested for energy storage, electromagnetic shielding, catalysis, and sensing — their versatility setting them apart as truly programmable matter.

The Breakthrough: When Entropy Took Over

For all their promise, MXenes remained bound to their origins — the ordered MAX phases from which they came. Most early versions contained only one or two metals, a symmetry that, while stable, also limited their potential. To break that ceiling, researchers from Purdue and Drexel decided to see how far they could push the lattice before it broke.

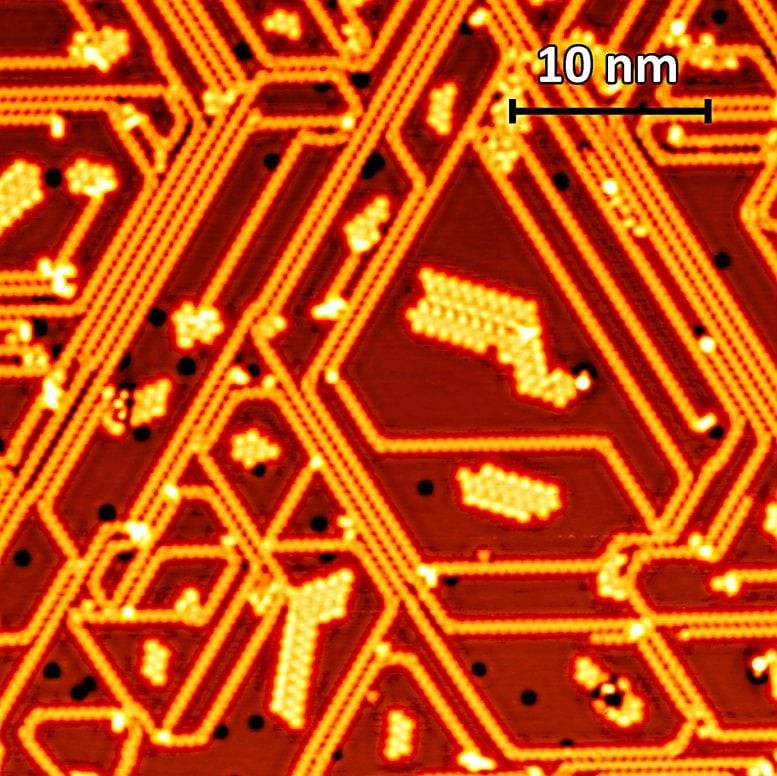

They created 40 new MAX-phase compositions, stacking between two and nine transition metals into a single structure. Each additional element introduced competing atomic preferences — some favoring one site, others another.

With up to six metals, the lattice behaved predictably: enthalpy — the energy favoring order — kept atoms organized. But when the mix grew to seven or more metals, the pattern broke. The structure no longer preferred one arrangement over another. Entropy, the measure of randomness itself, took control.

What should have collapsed instead stabilized. Etching these high-entropy MAX phases into MXenes erased the boundary between order and disorder, producing an atom-thin mosaic of metals. That disorder even shaped their chemistry — oxygen groups dominated the surfaces, while hydroxyl and fluorine faded away as metallic diversity increased.

Properties of Entropy-Forged MXenes

Despite their atomic chaos, these MXenes didn’t lose their metallic character. In fact, their electrical resistivity dropped sharply as the number of metals increased — in some cases, by nearly an order of magnitude. Infrared emissivity fell in tandem, pointing to materials capable of surviving the extremes of heat, radiation, and pressure.

What emerged wasn’t fragility, but resilience through complexity. The very act of pushing a structure beyond its comfort zone revealed a new design principle: that stability can be born from controlled disorder.

The implications reach far beyond the lab. By showing that disorder can be engineered, these MXenes open an entirely new frontier in materials science. Metallic, conductive, and water-dispersible, they endure where most materials fail — making them candidates for the toughest environments imaginable, from the vacuum of space to the crushing depths of the ocean and the corrosive interiors of electrochemical systems.

“We want to continue pushing the boundaries of what materials can do, especially in extreme environments where current materials fall short,” said Anasori.

MXenes’ story is still unfolding, but history suggests such breakthroughs rarely stay confined to the lab. Bronze ushered in civilization’s first tools and weapons. Steel built cities. Silicon powered the digital age. Now, MXenes may mark the next leap — materials designed not by resisting disorder, but by embracing it.

Source:NEW ATLAS

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2025), When Atoms Break the Rules: High-Entropy MXenes Challenge Materials Science, Upending Long-Held Theories, AnaTechMaz, pp. 289