Scientists Discover Hidden Atomic Structures in Everyday Metals, Upending Long-Held Theories

For Freitas—an early-career scientist—the discovery validates his decision to pursue a topic many believed had little room left for meaningful breakthroughs. He credits support from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research’s Young Investigator Program and the teamwork behind the project, which included three MIT PhD students as co-first authors: Mahmudul Islam, Yifan Cao, and Killian Sheriff.

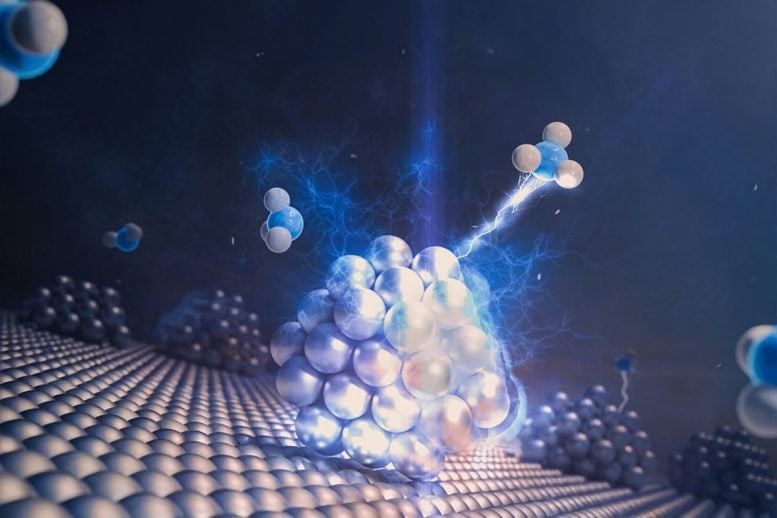

Figure 1. Hidden Atomic Patterns in Common Metals Rewrite Long-Standing Scientific Theories.

“There was a point when I wondered whether this was even worth tackling since so many researchers had already explored it,” Freitas recalls. “But the more I studied the problem, the more I realized that most prior work focused on idealized lab conditions. We wanted to simulate real manufacturing environments with high accuracy. What I love most about this project is how unexpected the results were—nobody anticipated that complete atomic mixing might be impossible.” Figure 1 shows Hidden Atomic Patterns in Common Metals Rewrite Long-Standing Scientific Theories.

Freitas and his team began with a simple, practical question: How quickly do chemical elements mix during metal processing? Traditionally, it was believed that metals eventually reach a completely uniform composition during manufacturing. By pinpointing when that happens, the researchers hoped to find a straightforward way to design alloys with varying degrees of atomic organization—known as short-range order.

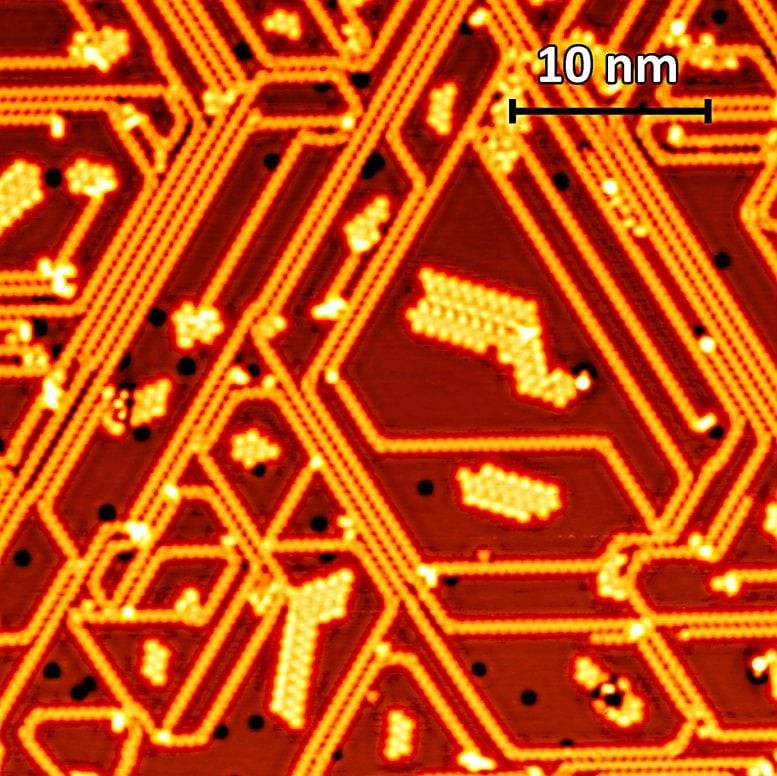

Using machine learning, the team simulated the movement of millions of atoms as they interacted under conditions resembling real metal processing.

“It revealed an entirely new aspect of physics in metals,” the researchers write. “This was one of those rare moments where applied research led to a fundamental scientific breakthrough.”

To uncover this new behavior, the team created advanced computational tools — high-precision machine-learning models to capture atomic interactions, and statistical methods to measure how chemical order evolves over time. Using these tools, they conducted large-scale molecular dynamics simulations to observe how atoms rearrange during real-world processing conditions.

Their simulations revealed familiar atomic arrangements at temperatures much higher than expected — and, even more remarkably, completely new chemical patterns that had never been seen outside of manufacturing environments. These previously unknown configurations, which the researchers called “far-from-equilibrium states,” marked the first time such atomic patterns were ever documented.

To explain these findings, the team developed a simplified model that mirrored the simulation results. It showed that the unexpected chemical patterns stem from microscopic defects known as dislocations — twisted, three-dimensional distortions within the metal’s atomic lattice. As the metal is deformed, these dislocations move and distort, dragging nearby atoms along. Conventional wisdom held that such movement erased any trace of order, but the researchers found the opposite: dislocations actually favor certain atomic swaps over others, creating subtle, organized patterns rather than pure randomness.

“These defects have their own chemical preferences that influence how they move,” Freitas explains. “They tend to follow low-energy pathways — when faced with breaking bonds, they break the weaker ones first. So the process isn’t completely random. That’s what makes this so fascinating: these are non-equilibrium states, similar to how living systems maintain balance. Just like our bodies stay at a steady temperature despite a changing environment, metals under these processing conditions maintain a delicate balance between disorder and an intrinsic drive toward order.”

Applying the New Theory

The team is now extending their work to study how these atomic patterns form under a wide range of manufacturing conditions. Their goal is to create a comprehensive “map” linking specific metal-processing steps to distinct chemical patterns — effectively revealing how different treatments shape a metal’s internal structure.

Until now, the idea of chemical ordering and its influence on material properties has mostly remained an academic curiosity. But with this new map, the researchers hope to give engineers practical tools to treat atomic patterns as design parameters — variables that can be intentionally adjusted during manufacturing to unlock new performance traits.

“Scientists have long studied how atomic arrangements affect metallic properties, especially in catalysis,” Freitas explains, referring to the process that drives chemical reactions. “Electrochemistry, for example, takes place on a metal’s surface and is highly sensitive to local atomic configurations. And there are other properties you might not expect to depend on these patterns, like radiation resistance — which is critical for materials used in nuclear reactors.”

“You can imagine the implications for fields like aerospace,” he says. “They rely on ultra-optimized alloys with very specific compositions. With advanced manufacturing, we can now combine metals that normally wouldn’t mix by deforming them together. Understanding how atoms move and rearrange during those processes is essential — it’s what allows us to achieve both strength and low weight. That’s why this discovery could be a real game-changer.”

Source:SciTECHDaily

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2025), Scientists Discover Hidden Atomic Structures in Everyday Metals, Upending Long-Held Theories, AnaTechMaz, pp. 288