Silly and Pompous’: Researchers React to Official New Virus Names

You might not recognize the name Beta coronavirus pandemicum, but there’s a good chance you’ve encountered it in the past five years—it’s the virus responsible for COVID-19, also known as SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related Coronavirus 2). SARS-CoV-2 is among thousands of viruses that recently received new species names as part of a sweeping overhaul of the virus naming system, a move that has left some scientists skeptical.

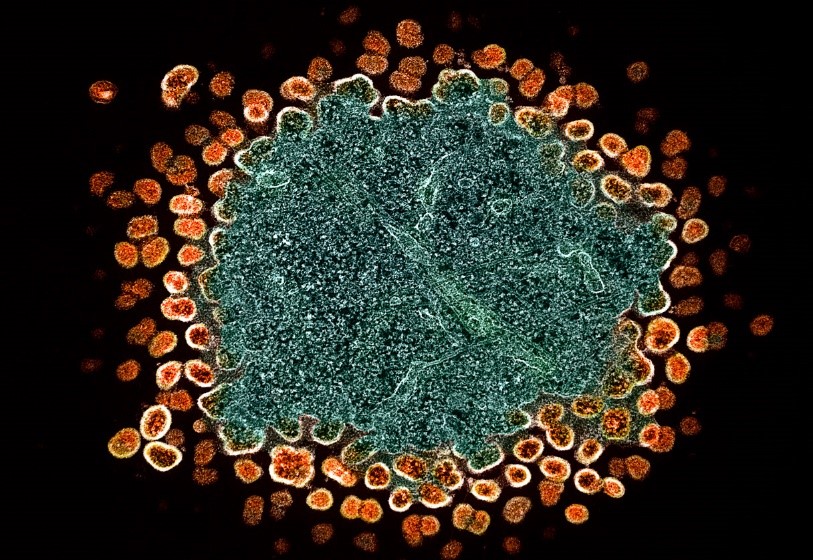

Figure 1. Silly and Pompous’: Scientists Criticize New Virus Naming System

The U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), which oversees repositories of virus sequences and related data, announced plans to add approximately 3,000 new Latinized names to its databases by spring 2025. This effort aligns with a naming system introduced by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) in recent years, albeit without much fanfare. Figure 1 shows Silly and Pompous’: Scientists Criticize New Virus Naming System. Figure 1 shows Silly and Pompous’: Scientists Criticize New Virus Naming System.

ICTV advocates for this change to address inconsistencies in virus naming. While NCBI’s adoption of the system will help mainstream the changes, some researchers remain unconvinced of their necessity—and a few even intend to disregard the new terms.

"Bog Huma Titanji, a physician-scientist at Emory University who studies the virus formerly known as HIV-1, expressed amusement and frustration at the revisions. “Longer Latin names that bear no resemblance to current terms seem more like distractions benefitting taxonomists than the broader scientific community,” she said. Titanji doubts she will ever adopt terms like Lentivirus humimdef1 for HIV, calling the revised names “a much-needed laugh.”

Currently, viruses are classified into families and genera, but their species-level naming is inconsistent. Names often reference associated diseases (e.g., SARS-CoV-2), hosts (e.g., eastern equine encephalitis virus), or geographic origins (e.g., Zika, named after a Ugandan forest)—an approach that can stigmatize.

This system worked when known viruses numbered in the hundreds or thousands, explains Murilo Zerbini, ICTV president and plant virologist at Brazil’s Federal University of Viçosa. However, genomic techniques now identify thousands of viruses in single studies, necessitating a standardized system to streamline scientific communication.

To address this, ICTV introduced a binomial naming convention—Latin genus and species names—aligning virology with broader biological taxonomy. After years of discussions and feedback, the system was approved in 2020, followed by extensive name development by expert groups. Zerbini hopes the new system will simplify scientists’ work.

Not everyone is convinced. Yale epidemiologist Nathan Grubaugh criticized the new names as “silly and pompous,” citing examples like Beta coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2), Orthoflavivirus nilense (West Nile virus), and the “really silly” Orthobunyavirus squalofluvii (Shark River virus). He argued the changes complicate rather than aid scientific work, adding that broader input from the scientific community was lacking.Zerbini, however, asserts that ICTV actively sought participation, holding consultations and delaying implementation to gather feedback. He notes that researchers are not obligated to use the new names exclusively, and NCBI will ensure the old names remain searchable in its databases.

Some scientists appreciate the effort. Stuart Ray, a virologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine, considers the new naming system a logical extension of existing taxonomy, unlikely to disrupt research. While the terms may not see widespread adoption initially, they could gain traction over time, particularly in centralized databases.

Confusion seems inevitable during the transition. For now, researchers must consult an Excel spreadsheet from ICTV to compare old and new names, although Zerbini acknowledges this solution is less than ideal. ICTV is working to improve search functionality.

Co-authors of the study include IU School of Medicine’s Michael Holmes, PhD, and Matheus S. Bastos, PhD. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Showalter Foundation.

Zerbini remains optimistic about the long-term benefits of the overhaul. “With any significant change, there’s resistance at first,” he said, noting that even the name human immunodeficiency virus faced pushback in the 1980s. “A few years from now, people will likely look back and wonder why this didn’t happen sooner.”

Source: Science

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2024), Silly and Pompous’: Researchers React to Official New Virus Names,AnaTechMaz, pp. 269