Toxoplasma Gondii Parasite Employs Unconventional Strategy to Produce Proteins for Drug Evasion

INDIANAPOLIS — Researchers from Indiana University School of Medicine have uncovered new insights into how Toxoplasma gondii parasites produce the proteins necessary for entering a dormant stage, which helps them evade drug treatment. Their findings were recently published with special distinction in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled parasite transmitted through cat feces, unwashed produce, or undercooked meat. It has infected up to a third of the global population, typically causing mild illness before entering a dormant phase within cysts throughout the body, including the brain.

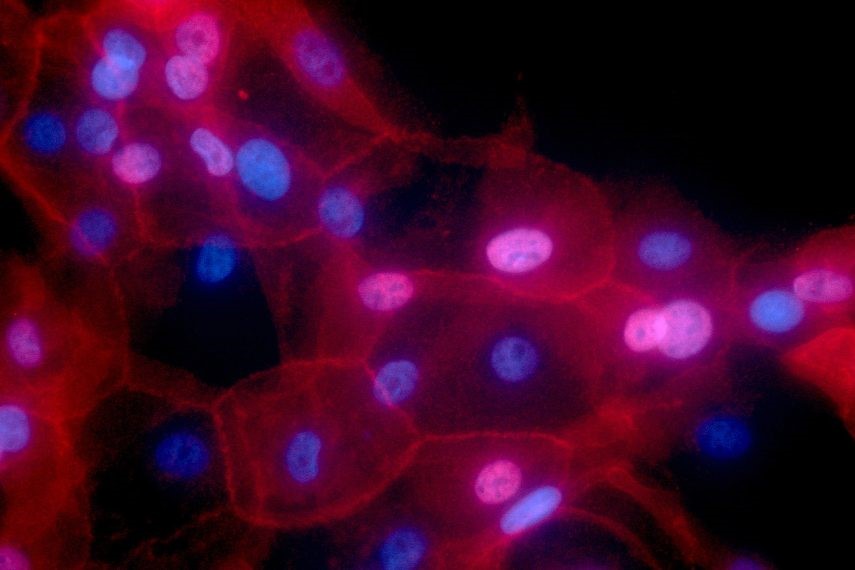

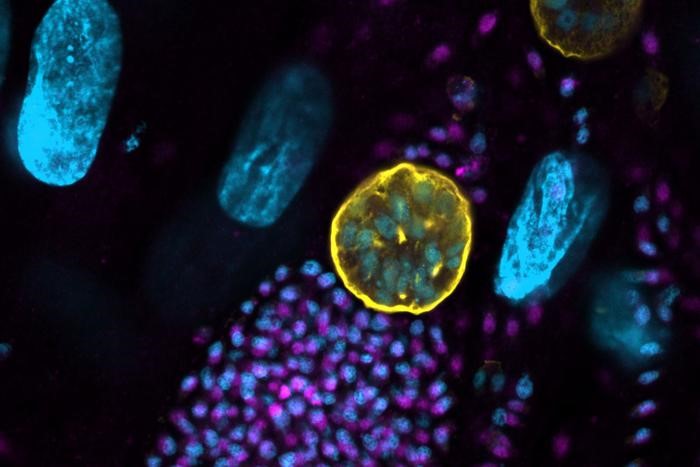

Figure 1. Toxoplasma gondii

These cysts are linked to behavioural changes and neurological disorders such as schizophrenia. They can also reactivate when the immune system weakens, leading to life-threatening organ damage. Although drugs can put toxoplasmosis into remission, there is no known cure. A better understanding of how the parasite forms cysts could lead to new treatment options. Figure 1 shows toxoplasma gondii.

Through years of collaboration, IU School of Medicine Showalter Professors Bill Sullivan, PhD, and Ronald C. Wek, PhD, have demonstrated that Toxoplasma alters its protein production when transitioning into cysts. These proteins, which are encoded by mRNAs, determine the fate of cells.

"Molecules of mRNA can be present in cells without being translated into protein," said Sullivan. "We’ve shown that Toxoplasma switches which mRNAs are translated into protein when forming cysts."

"mRNAs not only encode proteins but also contain leader sequences that regulate when mRNA is translated into protein," Dey explained.

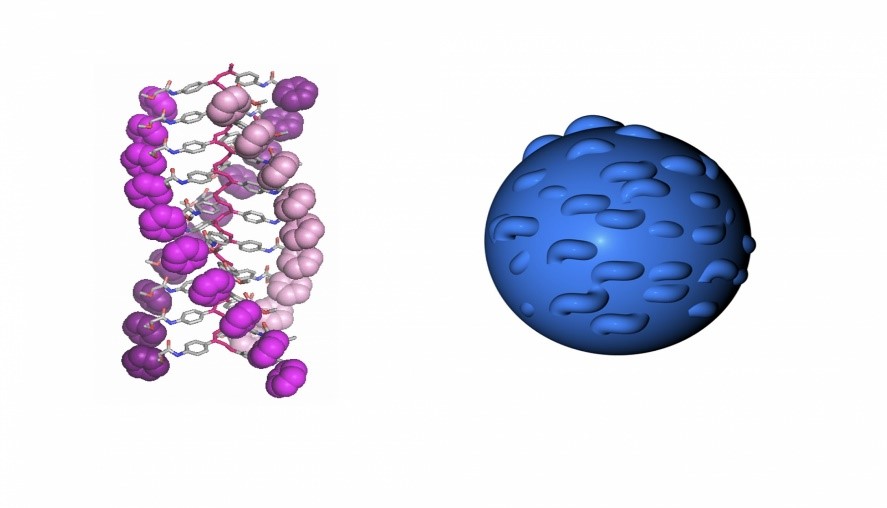

All mRNAs have a cap structure at the beginning of their leader sequence, which ribosomes use to bind and scan for the correct code to start protein synthesis. The team discovered that during cyst formation, BFD2 is translated into protein as expected. However, BFD1 follows a different mechanism, not relying on the cap structure for translation.

Instead, BFD1 is translated only after BFD2 binds specific sites within the BFD1 mRNA leader sequence.

This process, known as cap-independent translation, is typically seen in viruses, making its discovery in a microbe with cellular structures similar to human cells particularly surprising.

"Finding this mechanism in a microbe with cellular structures like ours suggests it has deep evolutionary roots," Sullivan said. "We’re also excited because the components involved don’t exist in human cells, making them potential drug targets."

The study was highlighted as an "Editor's Pick" in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, a distinction awarded to high-quality papers with broad interest to readers.

"This paper reveals how a parasite causing toxoplasmosis can respond to stress and thrive," said George N. DeMartino, PhD, associate editor of the journal. "This discovery provides a foundation for potential treatments, and a similar mechanism could be significant in cancer, indicating it may be a therapeutic target for various human diseases."

Co-authors of the study include IU School of Medicine’s Michael Holmes, PhD, and Matheus S. Bastos, PhD. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Showalter Foundation.

Source: EurekAlert

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2024), Toxoplasma Gondii Parasite Employs Unconventional Strategy to Produce Proteins for Drug Evasion, AnaTechMaz, pp. 268