This Ice Flows Like a Liquid but Remains Solid – Here's Why

Beyond the Ordinary: The Many Phases of Water

In daily life, we typically encounter water in three common states: solid, liquid, or gas. However, under extreme temperature and pressure, water can transform into several other, less familiar forms—some so unique that scientists refer to them as exotic phases. Now, using advanced neutron spectrometers and specialized equipment at the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL), researchers have experimentally observed one of these rare states for the first time: plastic ice VII.

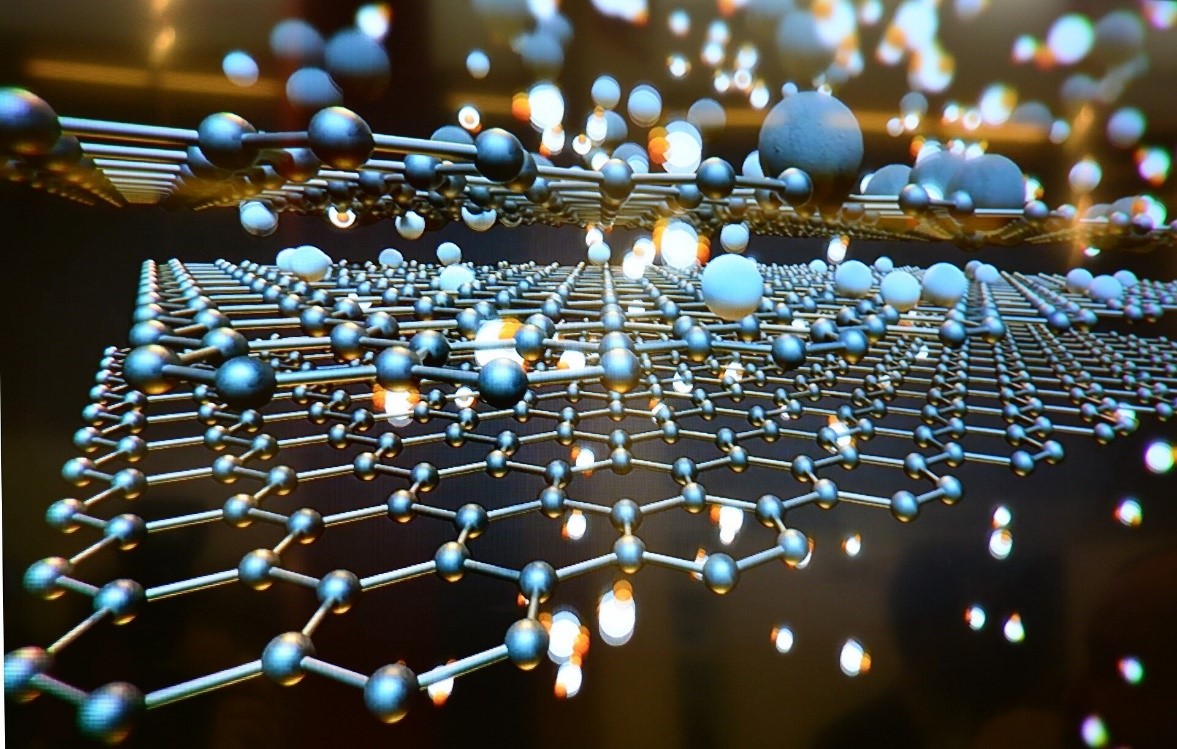

Figure 1. Solid Ice That Flows Like Liquid – The Science Behind It.

Unveiling Plastic Ice VII

Scientists first theorized the existence of plastic ice VII over 15 years ago using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. “Plastic phases are unique hybrid states that combine characteristics of both solids and liquids,” explains Livia Eleonora Bove, research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), associate professor at La Sapienza University in Rome, and associated scientist at EPFL in Switzerland. Figure 1 shows Solid Ice That Flows Like Liquid – The Science Behind It.

“In plastic ice, water molecules arrange themselves into a rigid cubic lattice, similar to ice VII, yet they also rotate rapidly—much like molecules in liquid water.”

Quasi-Elastic Neutron Scattering: Revealing Molecular Motion

To investigate the rapid motion of molecules, researchers utilized Quasi-Elastic Neutron Scattering (QENS), a technique particularly effective in detecting both translational and rotational dynamics.

“The ability of QENS to probe both types of molecular movement offers a distinct advantage over other spectroscopic techniques when studying exotic phase transitions,” explains Maria Rescigno, a PhD student at Sapienza University and the lead author of the study.

By adjusting temperature and pressure, the team identified three distinct states of water: liquid water, where molecules move freely in both rotation and translation; solid ice, where all molecular motion is frozen; and plastic ice VII, an intermediate phase where molecules retain a rigid structure but continue to rotate.

Extreme Conditions: Producing Plastic Ice VII

The experiments that led to the discovery of plastic ice VII were conducted using the time-of-flight spectrometers IN5 and IN6-SHARP at the ILL. Generating this exotic phase required extreme conditions, with temperatures ranging from 450 to 600 K and pressures between 0.1 and 6 GPa—up to 60,000 times atmospheric pressure.

Advancements in neutron spectroscopy, made possible by a long-term collaboration between Livia Eleonora Bove, CNRS research director Stefan Klotz, and ILL scientist Michael Marek Koza, enabled the implementation of such demanding thermodynamic conditions.

“The success of this study is rooted in the extensive expertise and specialized infrastructure developed over the years at the ILL, particularly in high-pressure sample environments,” emphasizes Koza. “Moreover, ongoing upgrades to ILL’s spectrometers—such as those made through the Endurance program—have enabled increasingly sophisticated experiments using state-of-the-art instrumentation.”

Challenging Expectations: New Insights into Molecular Dynamics

A detailed analysis of neutron scattering data revealed that the molecular dynamics of plastic ice VII may be more complex than initially predicted by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. “QENS measurements suggest a different molecular rotation mechanism for plastic ice VII than the free-rotor behavior originally expected,” explains Maria Rescigno.

Further MD simulations, combined with Markov chain analysis, provided a more refined understanding of water molecule dynamics. The most probable mechanism was identified as a 4-fold rotational model, a behavior typically seen in jump-rotor plastic crystals.

The Transition to Superionic Ice: Exploring the Unknown

To investigate the phase transition from ice VII to plastic ice VII, researchers conducted additional neutron and X-ray diffraction experiments—using the D20 diffractometer at the ILL and facilities at the Institute of Mineralogy, Physics of Materials, and Cosmochemistry (IMPMC).

“This transition is predicted to be either first-order or continuous, depending on the simulation method used,” explains Livia Eleonora Bove. “The continuous transition scenario is particularly intriguing, as it suggests that the plastic phase could serve as a precursor to the elusive superionic phase—another exotic hybrid state of water predicted at even higher temperatures and pressures, where hydrogen ions move freely within a stable oxygen lattice.”

Implications for Planetary Science and Beyond

Both plastic and superionic ice phases hold significant relevance for planetary science, potentially influencing our understanding of the internal composition and glacial dynamics of icy moons such as Ganymede and Callisto, as well as icy planets like Uranus and Neptune, where these phases may be prevalent.

Neutron scattering has not traditionally been a primary tool in planetary research. However, its unmatched ability to precisely map hydrogen positions and dynamics, along with recent advancements allowing experiments at pressures relevant to planetary interiors, has significantly expanded its impact in the field. As researchers push the boundaries of extreme conditions, even more exotic phases of water may yet be discovered.

Source: SciTECHDaily

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2025), This Ice Flows Like a Liquid but Remains Solid – Here's Why, AnaTechMaz, pp. 137