Cracks in the Cosmos: Unraveling the Inaccuracies in the Physics of Massive Stars and Supernovae

Scientists have discovered evidence that astrophysical models of massive stars and supernovae do not align with observations from gamma-ray astronomy.

The discovery was made after an international research team employed a groundbreaking experimental method to examine the uncertain nuclear properties of an unstable isotope.

Artemis Spyrou, a physics professor at Michigan State University (MSU) and the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), led an international team to investigate iron-60, a rare and unstable isotope, using an innovative experimental method. The research, conducted in collaboration with Sean Liddick, a chemistry professor at FRIB and head of its Experimental Nuclear Science Department, as well as 11 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers from FRIB, was published in Nature Communications.

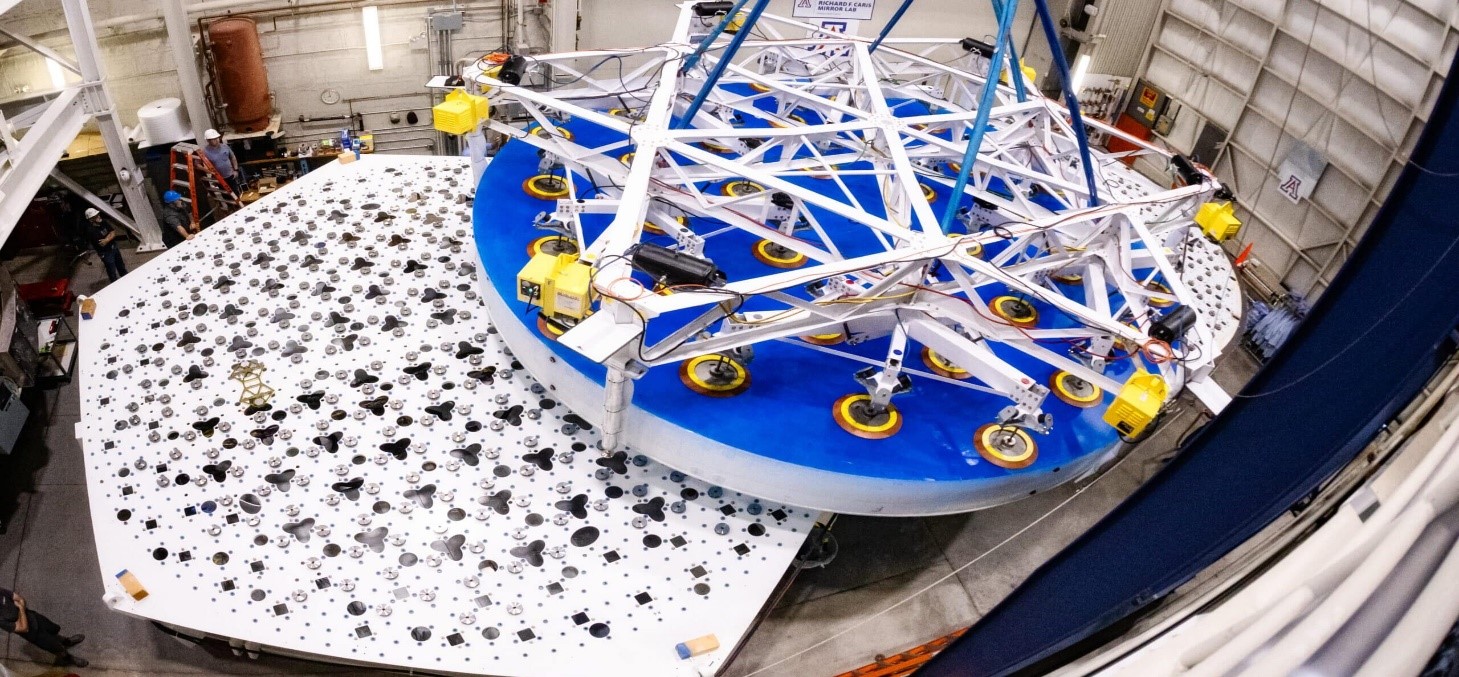

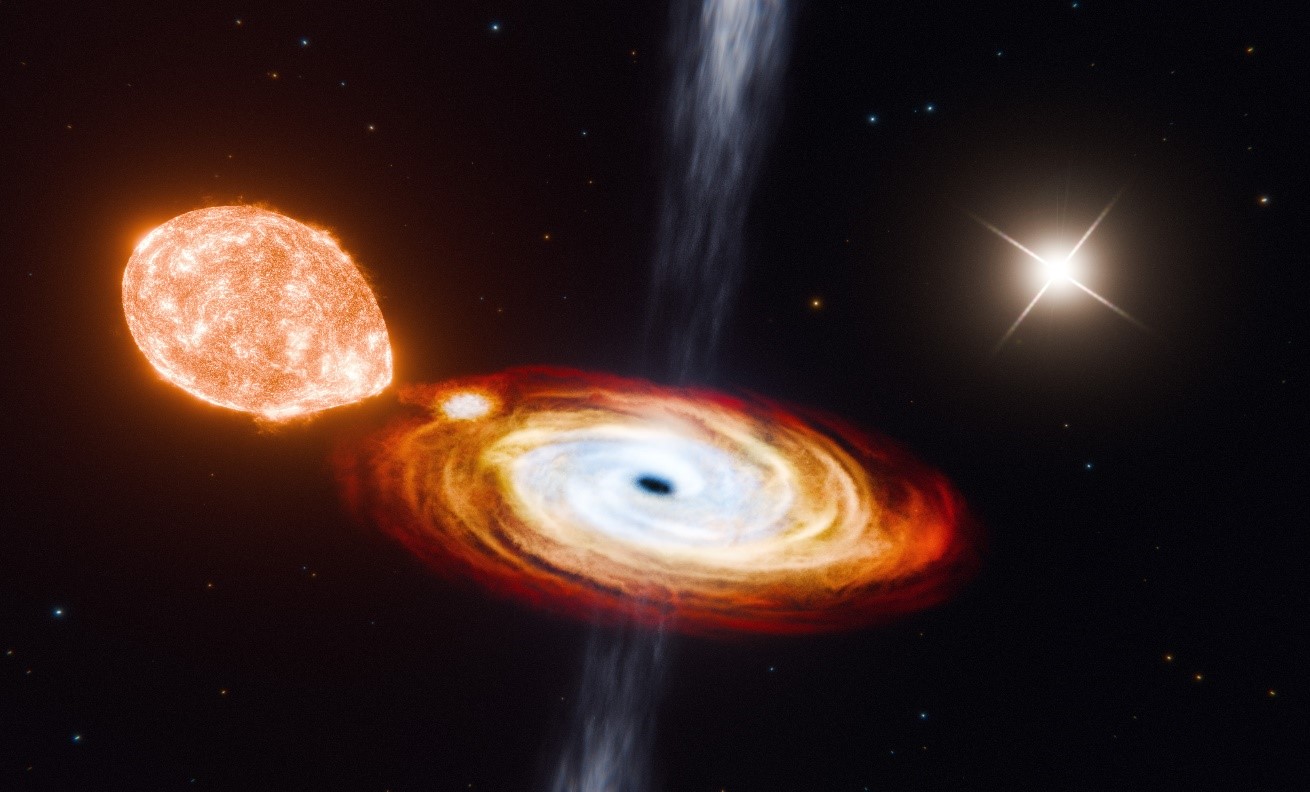

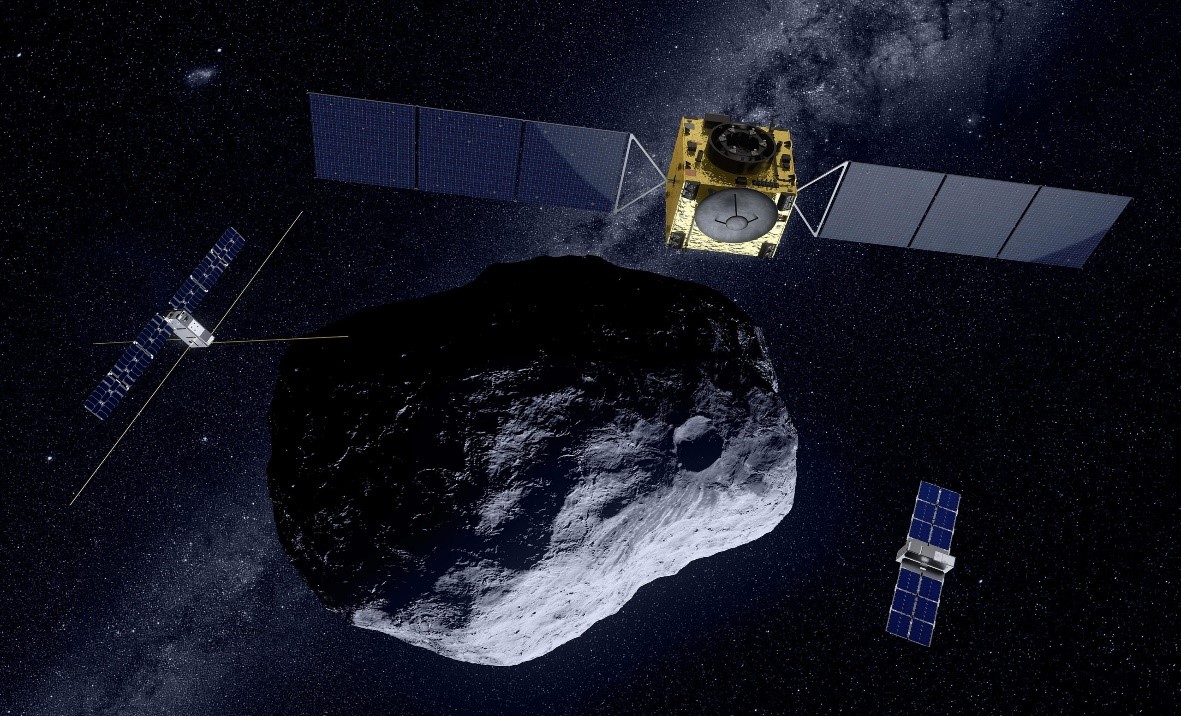

Figure 1. Iron-60 Study Challenges Supernova Models, Redefines Star Life Cycles

Exploring the Origins of Iron-60

Iron-60 has long fascinated astrophysicists because it is produced in massive stars and released into the galaxy during supernovae. To explore this rare isotope, Spyrou’s team conducted experiments at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, the predecessor to FRIB. Their innovative method was developed in partnership with Ann-Cecilie Larsen and Magne Guttormsen from the University of Oslo in Norway. Figure 1 shows Iron-60 Study Challenges Supernova Models, Redefines Star Life Cycles.

Iron-60 has long fascinated astrophysicists because it is produced in massive stars and released into the galaxy during supernovae. To explore this rare isotope, Spyrou’s team conducted experiments at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, the predecessor to FRIB. Their innovative method was developed in partnership with Ann-Cecilie Larsen and Magne Guttormsen from the University of Oslo in Norway. Figure 1 shows Iron-60 Study Challenges Supernova Models, Redefines Star Life Cycles.

Progressing Astrophysical Models

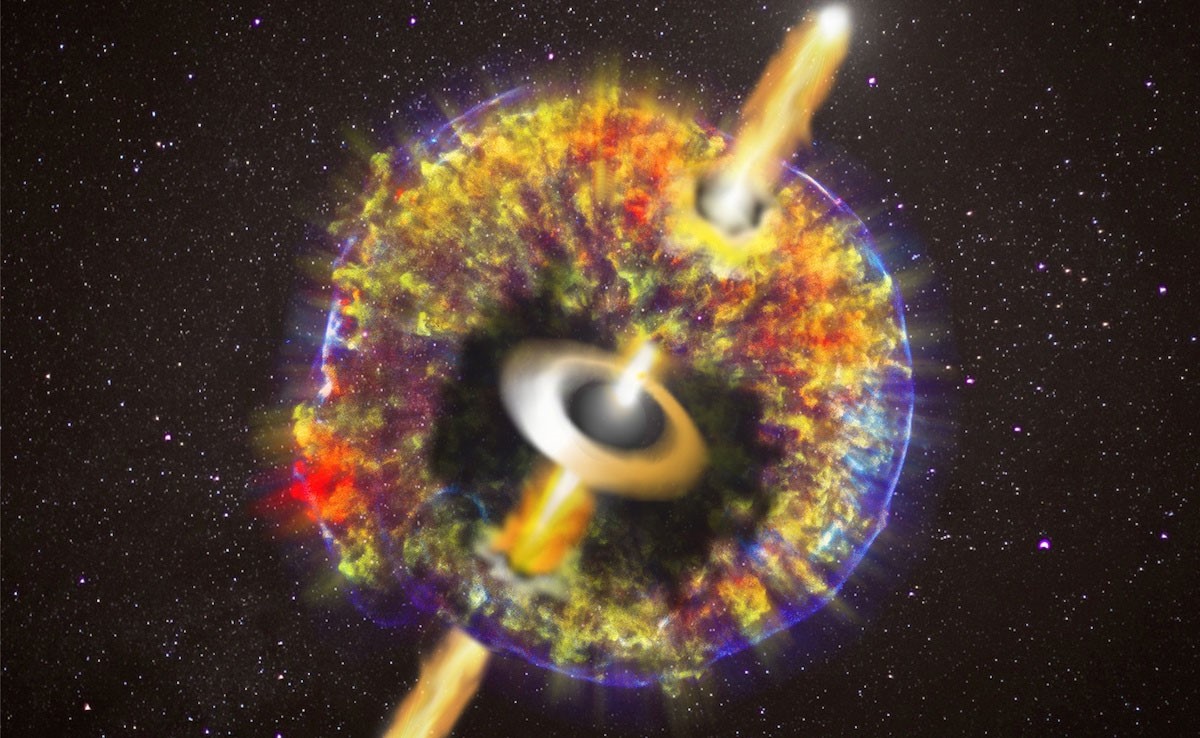

Iron-60, with a half-life of over 2 million years, provides a lasting signature of its supernova origin. As it decays, it emits gamma rays, which scientists measure to gain insights into stellar life cycles and the explosive deaths of stars. This data is crucial for refining astrophysical models.

“One of the main goals of nuclear science is to create a predictive model of nuclei that can accurately describe the properties of any atomic system,” said Liddick. “However, we’re not there yet, and we must experimentally measure these processes first.” To improve these models, scientists must produce rare isotopes, observe them, and then compare the results with predictions for accuracy.

“To study these nuclei, we can’t simply find them on Earth,” explained Spyrou. “We have to create them. That’s where FRIB’s expertise lies—producing stable isotopes, accelerating them, fragmenting them, and generating exotic isotopes, some of which may only exist for a few milliseconds, so we can study them.” To that end, Spyrou’s team designed an experiment with two objectives: first, to better understand the neutron-capture process that transforms iron-59 into iron-60, and second, to use the data to address longstanding discrepancies between supernova model predictions and the observed traces of these isotopes.

Leading the Way with the Beta-Oslo Method

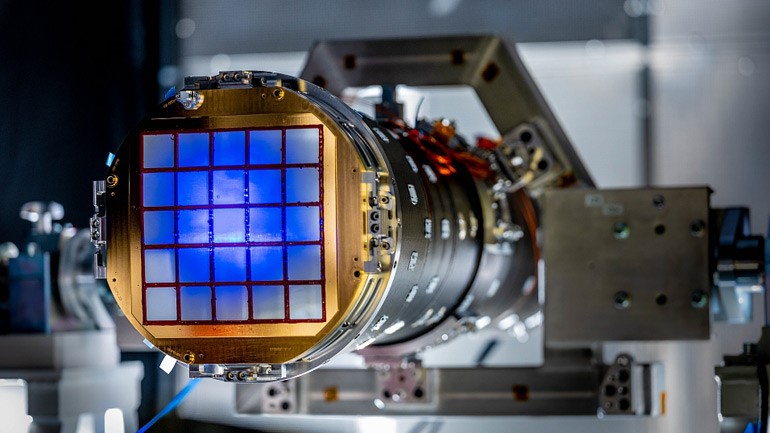

Iron-60 has a relatively long half-life, but its neighboring isotope, iron-59, is less stable, decaying within 44 days. This short half-life presents a challenge for measuring the neutron capture reaction on iron-59, as it decays before reliable measurements can be taken. To tackle this issue, the team developed an innovative approach. Collaborating with the University of Oslo, Spyrou and Liddick adapted the Oslo Method, originally created by co-author Guttormsen at the Oslo Cyclotron Laboratory. This method uses nuclear reactions to populate a nucleus for measurement, but it was traditionally limited to near-stable isotopes.

By combining expertise in detection, beta decay, and nuclear reactions, they introduced the beta-Oslo Method, a variation that employs beta decay itself to populate the target nucleus. This breakthrough allowed them to produce the desired isotope more efficiently and to study neutron-capture reactions on short-lived nuclei.

“The beta-Oslo method is still the only technique that can provide constraints on these very exotic nuclei far from stability,” said Spyrou.

Enhancing Stellar Models

After addressing critical uncertainties in the nuclear reaction network that produces iron-60, Spyrou’s team found that the likelihood of this reaction occurring within massive stars is up to twice as high as predicted by current models. This suggests that existing supernova models are flawed, and certain stellar characteristics are still inaccurately represented. In their paper's conclusion, the researchers proposed that resolving this issue might require adjustments in stellar modeling, such as reducing stellar rotation, assuming smaller mass limits for star explosions, or revising other stellar parameters.

This discovery not only has significant implications for understanding the inner workings of massive stars but also underscores the potential of the beta-Oslo Method as a valuable tool for future research. "This wouldn't have been possible without our partners at the University of Oslo, who sparked the idea for this collaboration during a 2014 seminar at MSU," said Liddick. "From there, we began discussing the possibility of using beta decay, and our partnership grew from that moment. I’m confident we will continue working together for many years to come."

Source: SciTechDaily

Cite this article:

Janani R (2024), Cracks in the Cosmos: Unraveling the Inaccuracies in the Physics of Massive Stars and Supernovae, AnaTechMaz, pp. 133