New Simulation Technique Enhances Our Understanding of The Earth's Interior

The Earth's magnetic field is crucial for supporting life, as it protects the planet from cosmic radiation and solar wind. This field is generated by the geodynamo effect. According to Attila Cangi, Head of the Machine Learning for Materials Design department at CASUS, "The Earth’s core is primarily composed of iron." As one moves closer to the core, both temperature and pressure rise. Higher temperatures cause materials to melt, while the increasing pressure keeps them solid. Due to these extreme conditions, the outer core is molten, while the inner core remains solid. The rotation of the Earth and convection currents cause electrically charged liquid iron to flow around the solid inner core, generating electric currents that produce the magnetic field.

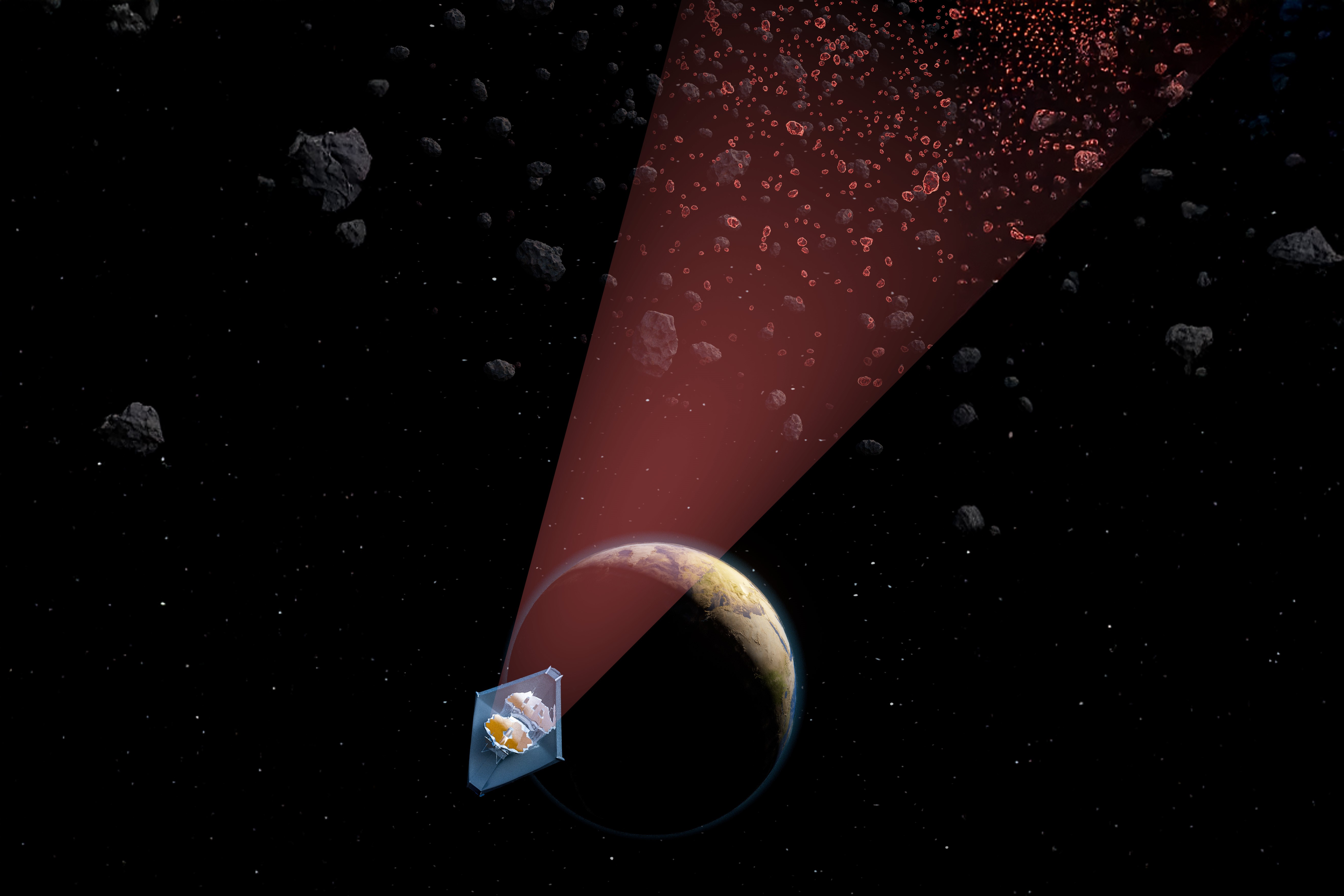

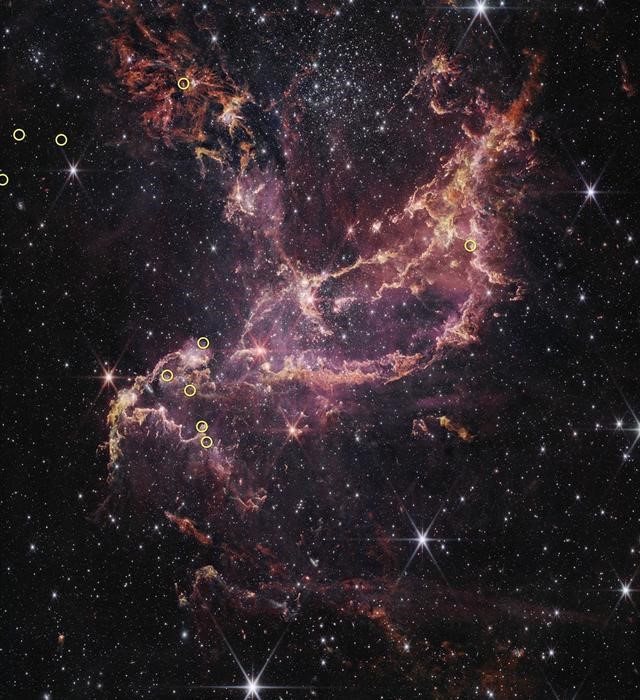

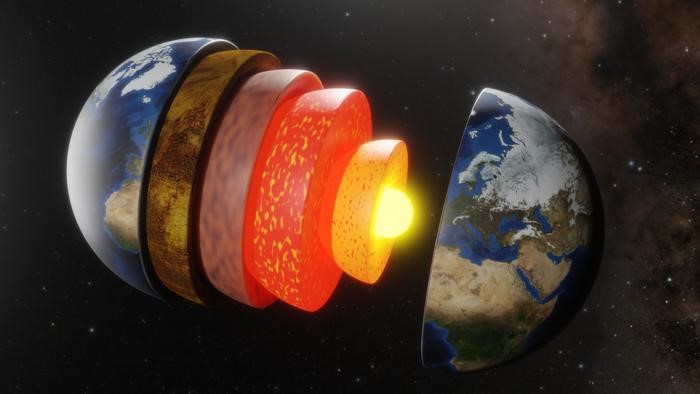

Figure 1. New Simulation Method Sheds Light on Earth's Interior.

However, key questions about the Earth’s core still remain. For example, what is the exact structure of the core, and what role do additional elements, thought to be present alongside iron, play? These factors may significantly influence the geodynamo effect. Scientists gain insights from experiments where seismic waves are sent through the Earth, and their "echoes" are detected using highly sensitive sensors. According to Svetoslav Nikolov from Sandia National Laboratories, "These experiments suggest that the core contains more than just iron. The measurements do not align with simulations that assume a pure iron core." Figure 1 shows New Simulation Method Sheds Light on Earth's Interior

Simulating Shock Waves on the Computer

The research team made notable progress by developing and testing a new simulation method. The innovation, called molecular-spin dynamics, integrates two previously separate approaches: molecular dynamics, which models atomic motion, and spin dynamics, which accounts for magnetic properties. As CEA physicist Julien Tranchida highlights, "By combining these two methods, we were able to investigate the effects of magnetism under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions on scales that were previously unreachable." The team simulated the behavior of two million iron atoms and their spins, examining how mechanical and magnetic properties interact. They also used artificial intelligence (AI) to determine atomic force fields with exceptional precision, requiring high-performance computing resources to develop and train the models.

Once the models were prepared, the team ran simulations on the digital model of two million iron atoms, representing the Earth’s core. They subjected it to the temperature and pressure conditions found deep inside the Earth by propagating pressure waves through the atoms, simulating their heating and compression. When the shock waves slowed down, the iron remained solid and adopted various crystal structures, but when the shock waves sped up, the iron became mostly liquid. The simulations also showed that magnetic effects significantly influence the material’s properties. Mitchell Wood, a materials scientist at Sandia National Laboratories, said, “Our simulations align well with experimental data and suggest that under specific temperature and pressure conditions, a particular phase of iron could stabilize and potentially affect the geodynamo.” This phase, called the bcc phase, has only been hypothesized, not observed experimentally under these conditions. If confirmed, the findings could help resolve several key questions about the geodynamo effect.

Energy-efficient AI Development

Beyond shedding light on the Earth’s interior, the method may also spark technological advancements in materials science. Cangi plans to apply the technique in both his department and through collaborations to model neuromorphic computing devices. These brain-inspired systems could process AI algorithms faster and more efficiently. The new simulation method could support the development of innovative, energy-efficient hardware solutions for machine learning by digitally replicating spin-based neuromorphic systems.

Another promising area of research is data storage. Magnetic domains on tiny nanowires could offer faster and more energy-efficient storage than conventional technologies. As Cangi explains, “There are currently no accurate simulation methods for either application, but I am confident that our new approach can model the necessary physical processes realistically, potentially accelerating the development of these IT innovations.

Source: EureAlert

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2024), "New Simulation Technique Enhances Our Understanding of The Earth's Interior", AnaTechMaz, pp. 146