RNA work that led to COVID-19 vaccines wins 2023 Nobel in medicine

In December 2020, the first vaccines based on a type of genetic material known as mRNA rolled out to fight COVID-19. That was less than 12 months after the lethal disease came to the world’s notice. Within a year, those new shots appeared to have saved nearly 20 million lives. Now, two biochemists who laid the groundwork for mRNA vaccines have been awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology.

They’re Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman. Both have spent many years working in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania, or Penn. Now Karikó is at the University of Szeged in Hungary (her native country) as well as at Penn. On Oct. 2, the pair learned they are sharing a Nobel for modifying mRNA in a way that makes it useful in medicine.

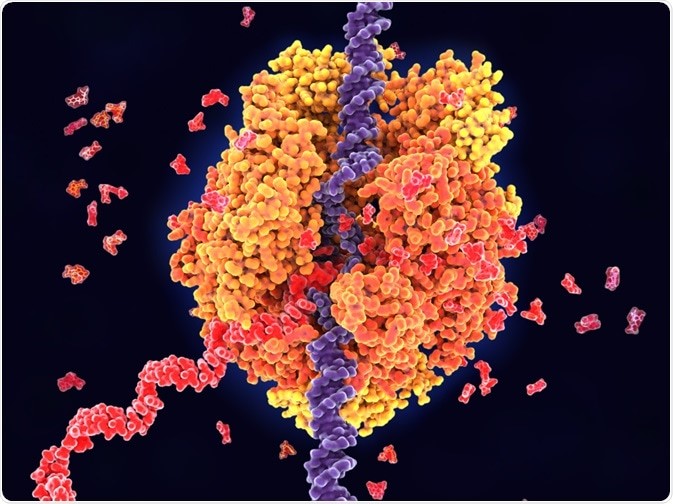

Figure 1. RNA work that led to COVID-19 vaccines wins 2023 Nobel in medicine

RNA work that led to COVID-19 vaccines wins 2023 Nobel in medicine is shown in Figure 1. Ultimately, their work could lead to other vaccines and to treatments for other infectious diseases and cancer.

It’s no exaggeration to say the COVID-19 pandemic “was a traumatic event,” said Qiang Pan-Hammarström. She’s a member of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute. It’s in Stockholm, Sweden. Her group awards the prize for medicine or physiology. The basic discovery by these two scientists “has made a huge impact on our society,” she says. Pan-Hammarström shared her comments after an Oct. 2 news briefing that named the winners.

As of March 2023, more than 13 billion jabs had delivered COVID-19 vaccines into the arms of people around the globe. In the United States, mRNA shots accounted for the vast majority of COVID vaccinations. There, the vaccines are believed to have prevented some 1.1 million COVID-related deaths and 10.3 million hospitalizations.

A different type of vaccine

RNA is DNA’s lesser-known chemical cousin.

DNA contains the genetic instructions for what the body’s cells should do. To carry out those tasks, cells start by making RNA copies of the DNA instructions. Some of the copies — known as messenger RNA, or mRNA — will be used to build proteins.

Proteins do much of the important work that keeps cells (and the organisms they’re a part of) alive and well. Messenger RNA “literally tells your cells what proteins to make,” says Kizzmekia Corbett-Helaire. She works at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. It’s in Boston, Mass. There, she studies how viruses and the immune system interact.

A long time coming

Karikó and Weissman’s partnership began in 1997. They met over a copying machine at Penn. Karikó would go on to tell Weissman about her work with RNA. He shared with her his interest in vaccines.

Although they worked in separate buildings, they eventually collaborated to solve a fundamental problem. Pumping normal mRNA into the body gets the immune system riled up — and in a bad way. It triggers a flood of immune chemicals that can turn on damaging inflammation. What’s more, this mRNA produces very little immunizing protein after being injected into the body.

But the researchers found a way around these problems. They started by swapping out one building block of RNA — uridine — for a tweaked version of the molecule. This dampened the bad immune reaction, the team reported back in 2005.

“The messenger RNA has to hide and it has to go unnoticed by our bodies (which are very brilliant at destroying things that are foreign),” Corbett-Helaire says. Those new tweaks proved important to helping the mRNA “hide while also being very helpful to the body.”

When injected in the body, their tweaked mRNA now produced lots of protein. This caused the immune system to build defenses against a target virus. The researchers shared their findings in 2008 and 2010.

This tweaking of mRNA’s building blocks is what the 2023 Nobel Prize honors.

Giving RNA its due

For years, “we couldn’t get people to notice RNA as something interesting,” recalled Weissman. He spoke at an Oct. 2 news conference at Penn. In the early 1990s, vaccines using the new technology failed several human trials. Most researchers gave up on it.

But then Karikó “lit the match,” Weissman said. “We would talk about all the things that we thought RNA could do,” he recalled. Together, he said, they realized “how important it had the potential to be. That’s why we never gave up.”

Along the way, Karikó and Weissman started a company. Called RNARx, it aimed to develop mRNA-based treatments and vaccines.

Karikó later joined the German company BioNTech. But she and Weissman continued to work together. In 2015, they were part of a team that encased mRNA in bubbles of lipids, which are fatty compounds. This helped keep the body from breaking down the fragile RNA before it could get into cells.

The researchers then began developing their first mRNA vaccine — for Zika. Suddenly, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. At once they changed their focus. They now applied all they had learned to making a vaccine against COVID-19.

Source:Snexplores

Cite this article:

Gokula Nandhini K (2023), RNA work that led to COVID-19 vaccines wins 2023 Nobel in medicine, AnaTtechmaz, pp.751