Can Viruses Make Sounds? Scientists Use Light to Hear Life’s Hidden Vibrations

Harel is pioneering new microscopy techniques that enable researchers to observe molecular and atomic landscapes in motion rather than as static images. This innovative work has earned Harel MSU’s 2023 Innovation of the Year award and the university’s first-ever grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation.

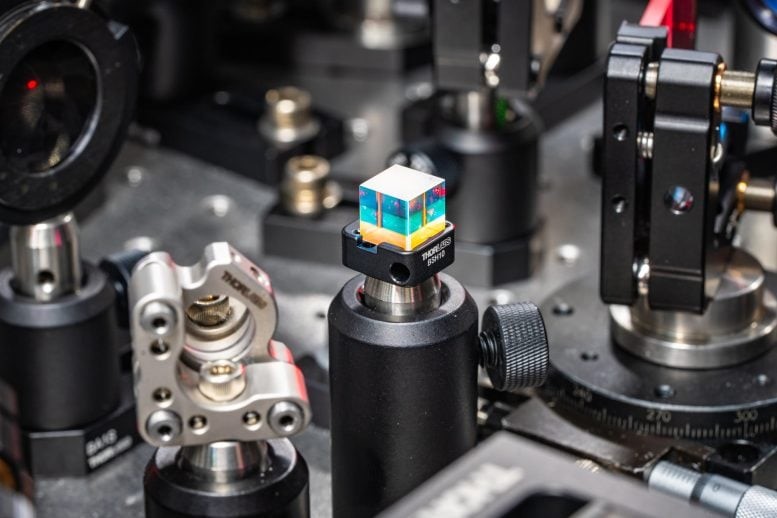

Figure 1. Listening to Viruses: Using Light to Reveal Life’s Hidden Vibrations.

Collaborating with Dohun Pyeon, a professor in MSU’s Department of Microbiology, Genetics, and Immunology (MGI), Harel’s lab leveraged expertise in virology to target and study virus particles.

"Teamwork is crucial in this challenging yet exciting project, and it’s fascinating to experimentally observe the nanoscale motion of these tiny virus particles—they are actually ‘breathing’ under laser illumination,” said Yaqing Zhang, a postdoctoral researcher in the Harel lab and the study’s first author.

Zhang expressed confidence that this technique could be widely applied to millions of viruses and other biological samples, yielding invaluable information. “The more we understand them, the better we can prepare for the next pandemic,” he added.

Few would think to link “virus,” “light,” and “listen” together—can you explain the science behind this breakthrough?

This discovery is rooted in the fundamental concept that every system, from stars to viruses, has a natural vibrational frequency. Essentially, all atoms within a material vibrate together, much like balls connected by a complex network of springs. These vibrations give each material a unique “sound,” just as a voice carries distinctive characteristics that allow us to recognize a speaker from across a room.

While researchers have previously studied ultrasonic vibrations in metal nanoparticles, Harel and his team explored whether biological systems also produce sounds when subjected to external forces. To test this, they used short pulses of light to generate coherent motion within a system, then followed up with a second pulse to capture that motion at different points in time. By compiling these snapshots, they created a "molecular movie" that reveals the vibrational motion of the object—ultimately leading to the discovery that viruses have their own unique sound signatures.

This method of "listening" to biological systems provides a dynamic alternative to traditional analysis techniques like electron microscopy (EM). While EM is highly detailed, it captures static snapshots in environments unlike those where living organisms naturally exist—such as in vacuums or at extremely low temperatures in cryo-EM. The goal of the Keck Foundation-supported research was to develop microscopy techniques that allow scientists to visualize and track biological processes in real-world conditions, where life thrives in a hot and wet environment.

Over several years, we refined increasingly sensitive techniques to measure acoustic vibrations, particularly at the single-particle level. This work was done in collaboration with the Pyeon lab in MGI, which provided access to various viruses for study.

Beyond detecting these vibrations, we also explored how this acoustic approach could serve as a powerful imaging tool without the need for traditional labeling. Labeling involves attaching markers to molecules to track their behavior, a process that, while highly specific, can be slow and labor-intensive.

Our goal is to demonstrate that this new methodology can leverage a viruses or molecule’s natural “labeling”—essentially, the unique sound of its own materials—to distinguish it from everything else in a system.

What do these viruses sound like? Do they ever change their tune?

The vibrations we detected occur in the gigahertz range, which is an extremely low frequency compared to optical transitions. For context, visible light falls in the hundreds of terahertz, meaning these acoustic signals are thousands to millions of times lower in energy than typical optical spectroscopy measurements.

In our study, we demonstrated that we could track individual viruses and even listen to a virus as it ruptures. As the virus begins to break apart and weaken, its acoustics shift to lower frequencies—almost like the sound of a balloon deflating.

What’s next for this research?

Our next goal is to dynamically track how a virus moves in real time. Currently, observing a virus entering a cell is an extremely slow and complex process, often requiring electron microscopy or intricate fluorescence labeling. We aim to develop a method that allows us to follow this process with far greater efficiency and detail.

For instance, we have a grant with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which focuses on biological and chemical detection. Part of their work involves developing antiviral drugs to combat infections.

The key question is: Can this technique accelerate that development process? By enabling us to observe a virus’s entire life cycle in real time, this method could offer valuable insights into how antivirals or drugs interfere with viral activity, ultimately leading to more effective treatments.

Source: SciTECHDaily

Cite this article:

Priyadharshini S (2025),”Can Viruses Make Sounds? Scientists Use Light to Hear Life’s Hidden Vibrations", AnaTechmaz, pp.1096